Antibiotic resistance has been on the tips of everyone’s tongues next to climate change for the past decade. But do people know what it is and why it’s such a big deal?

Im sure you’re snarking at me right now thinking of course I know what antibiotic resistance is… and if so, well done, you’re in the majority, as is shown in a survey conducted by the UK government in 2017 where 71% of people agreed with the statement ‘taking antibiotics when you don’t need them encourages bacteria that live inside you to become resistant’. But an alarming number of people are uninformed about antibiotic resistance with 34% agreeing with the false statement ‘antibiotic resistance is not caused by taking antibiotics’. Demographic data showed younger adults were less knowledgeable about antibiotic resistance compared to older groups (1). This is rather alarming considering this is the demographic whose lives will be most affected by the antibiotic resistance crisis. This really highlights the need, as pointed out by Adam Brimelow in BBC report in 2015, for improved education in schools about antibiotic resistance (2) targeting age groups at GCSE and younger.

Although most of the public understand that taking antibiotics when you don’t need them encourages bacteria to become resistant, a smaller percentage know exactly how this happens. Agricultural and medical overuse of antibiotics has placed selection pressure on bacteria living in the environment and within our own bodies. Overtime this has caused evolution to select for bacteria which encode molecular mechanisms that favour antibiotic resistance, increasing bacteria’s likelihood of survival… as just like us, their goal is to live in the end…

Metabolic processes of antibiotic resistance

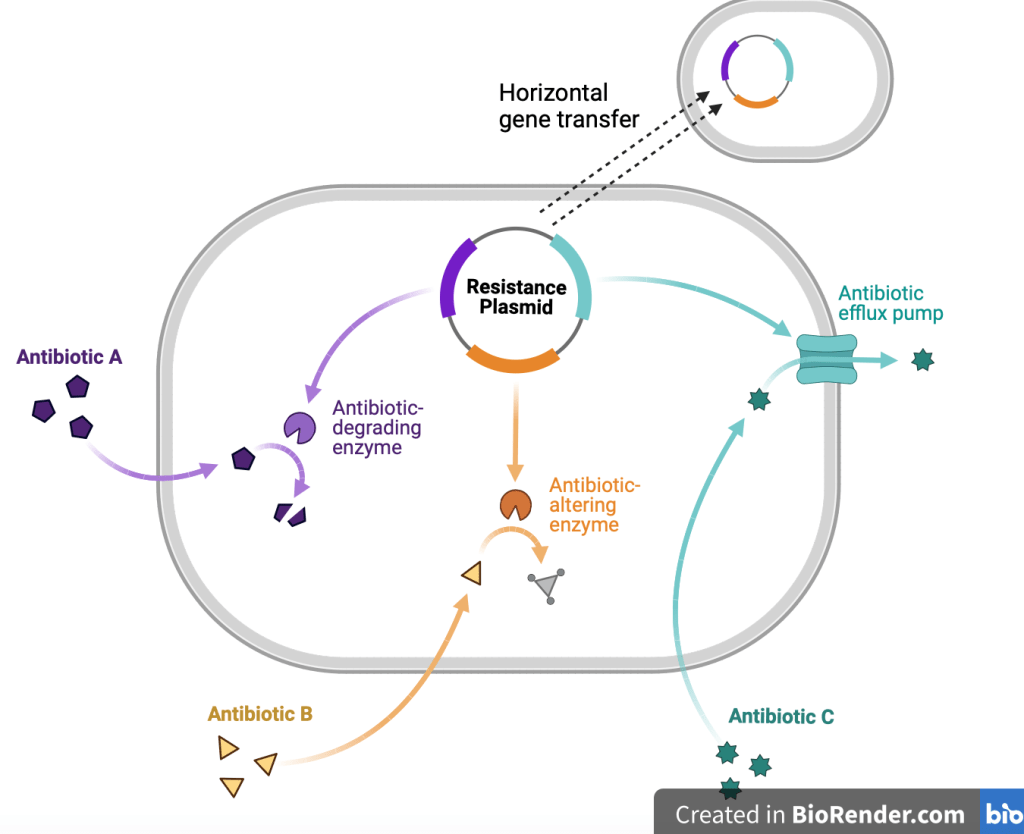

These molecular mechanisms include drug target modification, enzymatic inactivation, efflux pumps and metabolic bypass. Now if your knowledge of biology doesn’t extend to A level or degree you may be thinking, what does any of this actually mean?

Modification of drug target:

Enzymes deactivate antibiotics by altering their structure. Think about a lock and key, both fit perfectly and harmoniously together but what would happen if a part of your key broke? They would no longer fit together. This analogy can be used to understand how the modification of a drug target results in reduced functionality of the drug. Let’s look at the example beta-lactamase, an enzyme that binds to an antibiotic called beta-lactam. When it does this it cleaves (removes) a key ring structure in the molecule. Simultaneously an acetylating enzyme adds acetyl groups to free hydroxy groups of chloramphenicol). This causes a structural change rendering the antibiotic non-functional as it no longer ‘fits’ to its target (3) just like an altered key no longer ‘fits’ into a lock.

Enzyme inactivation:

High concentrations of antibiotics can trigger random mutations which result in the production of altered RNA polymerase (an enzyme which catalyses the synthesis of an RNA strand from a DNA template during prokaryotic transcription). This is relevant as antibiotics such as rifampin treat bacterial infections by inhibiting RNA polymerase by binding to the subunit within the DNA/RNA channel (5). The mutated RNA polymerase has been seen to be unaffected by rifampin in bacteria such as E. coli, resulting in continued bacterial growth.

Efflux pumps:

Efflux pumps are natural processes in bacteria that have always been present. Their role is to ‘pump’ toxins out of the bacteria (much like our liver does after a long night out), so naturally they also pump antibiotics out of bacterial cells, reducing their concentration in the cell and consequentially their toxicity. Efflux pumps are particularly beneficial to the bacterial cell as they pump out multiple classes of antibiotics, enabling multi-drug resistance (3). An example of this is E. coli’s ability to pump out tetracycline from its cells, making it resistant to the drug.

Horizontal gene transfer:

Shown and labelled in the diagram above, horizontal gene transfer enables bacteria to ‘spread’ their resistance through transferring resistance genes to surrounding bacteria, amplifying the problem of antibiotic resistance.

Metabolic bypass:

Have you ever heard of bacterial biofilms? These are congregations of bacteria forming a large population which is metabolically inactive in the centre, making them unresponsive to antibiotics which rely on targeting metabolically active processes. The close proximity of bacterial cells within a biofilm increases the rate at which horizontal gene transfer occurs. Persister cells add to the issue by lying dormant during antibiotic treatment, only to become active again after the antibiotic is removed, resulting in relapse of infection.

what does all this mean?

Though traditionally it has been thought that reducing the amount of antibiotics used to below the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) would reduce the likelihood of bacteria developing antibiotic resistance, studies such as that of Stanton and colleagues have shown that evolutionary selection for antibiotic resistance occurs even at low concentrations of antibiotics (lower than the MIC) (4) showing that any use of antibiotics is ultimately unsustainable.

You may be thinking what does this means for the future? Will we be able to treat infections at all? A future without antibiotics is quite scary…

But it doesn’t need to be so bleak! The answer to antibiotic resistance is using alternative treatment methods such as bacteriophages, CRISPR Cas9 gene editing, targeting virulence factors, and combination therapies. Pharmaceutical companies have already shifted drug development funding from the creation of new antibiotics onto investigating alternative treatment methods for bacterial infections, kick starting a new era of treatment for bacterial infections!

If you’re interested in reading about how bacteriophages could be our answer to antibiotic resistance check out ‘Bacteriophages, The Future of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Treatment’.

Written by Francesca Giannachi-Kaye

Biological Sciences graduate from the University of Exeter

Reference List

- McNulty. What the public know about antibiotic use and resistance, and how we may influence it. public health England. 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933982/Capibus_knowledge_and_behaviour_report.pdf

- Brimelow. Calls for schools to educate children about antibiotic resistance. 2015. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-34183475

- Madigan, Bender, Buckley, Sattley, Stahl. Brock Biology of Microorganisms. 6. United Kingdom: Pearson Education Limited; 2022

- Stanton, Murray, Zhang, Snape, Gaze. Evolution of antibiotic resistance at low antibiotic concentrations including selection below the minimal selective concentration. Communications biology. 3/9/20. 3. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-020-01176-w

- Drew. Rifamycins (rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine). 2022. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/rifamycins-rifampin-rifabutin-rifapentine