We have all heard of Net Zero. If not from our prior blog post on the topic you’ve likely heard politicians talk about it, seen it plastered on the news and maybe heard your neighbour nattering on about investing in an electric car…

But why should we even be thinking about net zero? What does it mean and what could be the repercussions if we were to scrap it all together.

What does Net Zero mean?

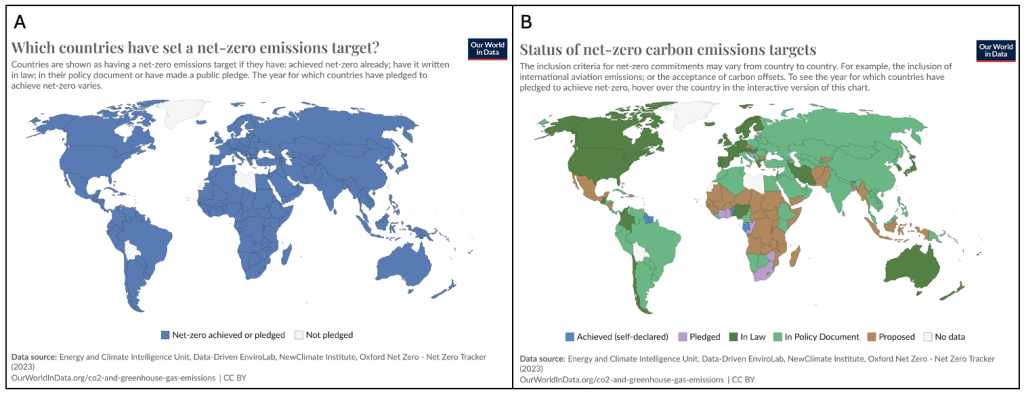

In simple terms, net zero means no longer adding greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere, so the amount of greenhouse gasses being added to the atmosphere would equal the amount being removed (1,3). In net zero, carbon emissions are still generated, the difference is there is no surplus of carbon in the atmosphere (3). Maps from ‘Our World in Data’ show most countries have either pledged or achieved implicating Net-Zero targets and many of them have either already implemented laws or are in the process of policy development to achieve their goals.

The UK is an example of a country that has implemented policies to achieve Net Zero by 2050. Some examples of the policies include:

- Utilizing new ways of generating electricity through wind and solar (5).

- Making 80% of new car sales zero emission by 2030.

- Installing 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028.

- Capturing and storing 20-30 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year by 2030 (1). Capturing and storing carbon dioxide can be done through reforestation and by utilizing new carbon capture methods like post-combustion, oxyfuel and pre-combustion (4).

If you think this sounds ambitious, you would be correct. Though the UK has cut back carbon emissions by 50% since the ’90s (1), mostly due to reducing fossil fuel use (6), a BBC news article published in December 2023 highlighted how the UK may not meet their 2030 target due to:

- Rishi Sunak’s delay on the ban of new petrol and diesel cars to 2035.

- The exemption of 20% of houses getting electric heat pumps.

- The granting of 100 oil and gas production licences for the North Sea (7) (burning of Rosebanks reserves would produce over 200 million tonnes of carbon dioxide).

- Installation of only 70,000 electric heat pumps in 2022 (530,000 off target).

- The cancellation regulations that would have required landlords to improve the energy efficiency of privately rented homes in 2023 (7).

To put it all into perspective, over 30 years the UK has reduced carbon emissions by 50%, under the Paris Climate Agreement the UK has to further reduce carbon emissions by 68% by 2030 (1). Subsequently, the Climate Change Committee has stated the UK’s ability to reach its targets by 2030 is unlikely.

What would a world without Net Zero look like?

Current climate policies will cause a warming of 2.7-3.1 degrees Celsius by 2100, 2x the target implicated by the Paris Agreement (3). If countries are not able to meet the current climate policies, temperatures are predicted to increase by 4.1-4.8 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times (3). Ultimately, a world without net zero would mean rapid increases in global temperatures. This is because greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane increase the earth’s surface temperature by trapping thermal energy that is emitted from the earth causing it to be reabsorbed by the Earth’s surface (11). Therefore, increased concentrations of greenhouse gasses cause increases in temperature, rainfall, summertime, droughts, more frequent and stronger hurricanes, tornadoes (14) and forest fires (11).

Fun Fact: in the early stages of Earth’s history the Sun provided less energy than it does today, high levels of nitrogen gas in the atmosphere helped warm the Earth, preventing the Earth from being permanently glaciated. In this case, the greenhouse gas, nitrogen helped make the Earth habitable for terrestrial plants (12).

Warming temperatures can have detrimental effects on the environment by causing climate shifts. This is where previously cooler areas become warmer, causing habitat change and putting significant pressure on the organisms that live within them. A common example of this phenomenon is the increased violence of storm events and the melting of sea ice causing polar bear populations to move into land (13). Another example that is discussed at length in our podcast titled: ‘Why are reefs dying? Saving Coral Reefs’ is the expulsion of zooxanthellae from coral polyps due to the stress induced by temperature rise resulting in mass coral bleaching events and the loss of coral habitats and the ecosystem services they provide. The loss of habitats like these will not only have massive implications for wildlife but also for people. There are a multitude of ways in which climate change impacts people, but one of the lesser-understood impacts of climate change is how it will result in the increased prevalence of tropical diseases and the likelihood of pandemics.

How does climate change impacts disease?

Climate change causes species to migrate into new areas, bringing disease with them:

Climate change is likely to cause the re-emergence of viral, bacterial and parasitic diseases in Europe and North America (20) because the distribution of disease across the world is determined by climate. Increased temperatures from global warming impact the geographical distribution of animals that carry diseases like insects, rodents and birds (20). An example is malaria carried by mosquitos. The highest transmission of malaria is typically in Africa, South of the Sahara and in parts of Oceania (21) but recently, mosquitos that transmit malaria have been expanding their ranges into warming areas which are newly suitable for mosquitoes (16). The shift of mosquitos carrying malaria into new areas results in new populations of people being exposed to the parasite. But it is not just malaria which is likely to increase as a response to climate change. Other mosquito-born infections like Dengue, chikungunya and Zika viruses (16) are likely to become more prevalent as mosquitos increase their range.

“The changing climate poses a substantial risk to progress against malaria, particularly in vulnerable regions. Sustainable and resilient malaria responses are needed now more than ever, coupled with urgent actions to slow the pace of global warming and reduce its effects,”

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General (15)

Mammals are also expanding their ranges such as in the case of birds. The Zoonotic bacteria Chlamydia can be carried by birds and according to the WHO infects 92 million people per year (20). As this disease is associated with bird migration, climatic factors that cause shifts in their migration patterns will subsequently cause shifts in disease distribution. Bats are also a common source of zoonic viruses like coronaviruses and Ebola (19). Their ability to disperse quickly into new areas (17) with new species has highlighted them as a likely source of future disease outbreaks, Carlson and colleagues predicted Central Asia will experience the greatest emergence of new viruses due to the diverse populations of bats that reside there (18).

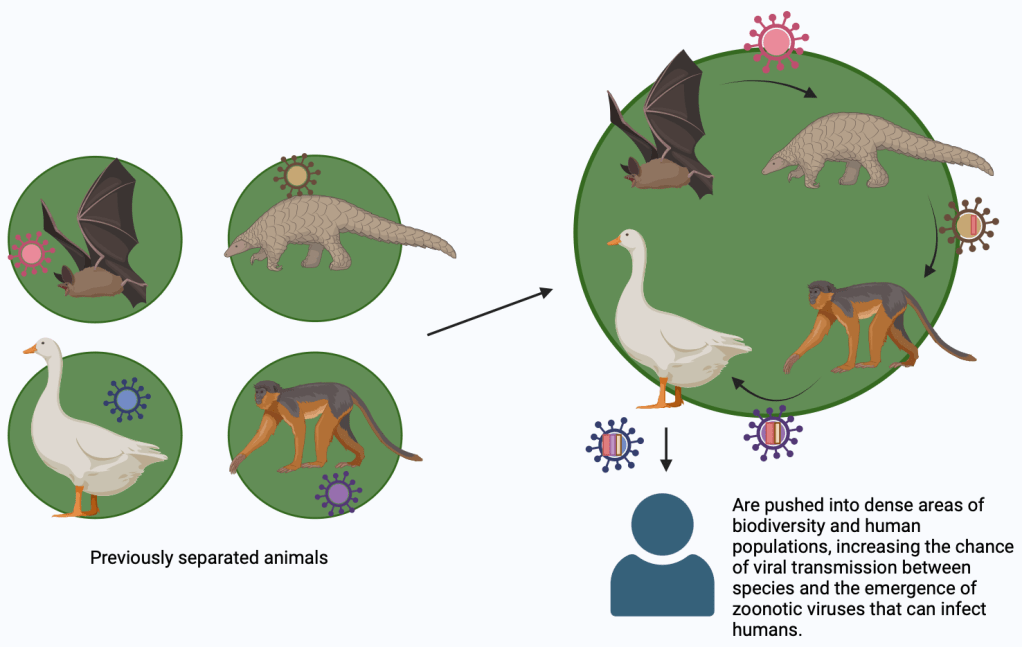

The loss of habitats will result in newly densely populated areas, increasing the likelihood of virus transmission between species:

Take the example of the polar bear mentioned before. As polar bears migrate inland they encounter new species which they had previously been isolated from. This means disease being carried by the polar bears or new species can now pass between them.

Ultimately, this does not just affect animal populations but also humans. Carlson and colleagues investigated how mammalian species may move in response to climate change and predicted different species are likely to be forced into areas of high biodiversity and human population density (17). This is problematic as each species carries viruses that have previously been isolated from other species, these viruses are likely to be shared between mammalian species due to climate change pushing them closer together, resulting in the emergence of new zoonotic viruses which could infect humans (17). Some examples of zoonotic viruses are HIV, Ebola, Rabies, Lyme disease and COVID-19.

The densely populated areas will increase the likelihood of transmission between animals and people, increasing the risk of new pandemics:

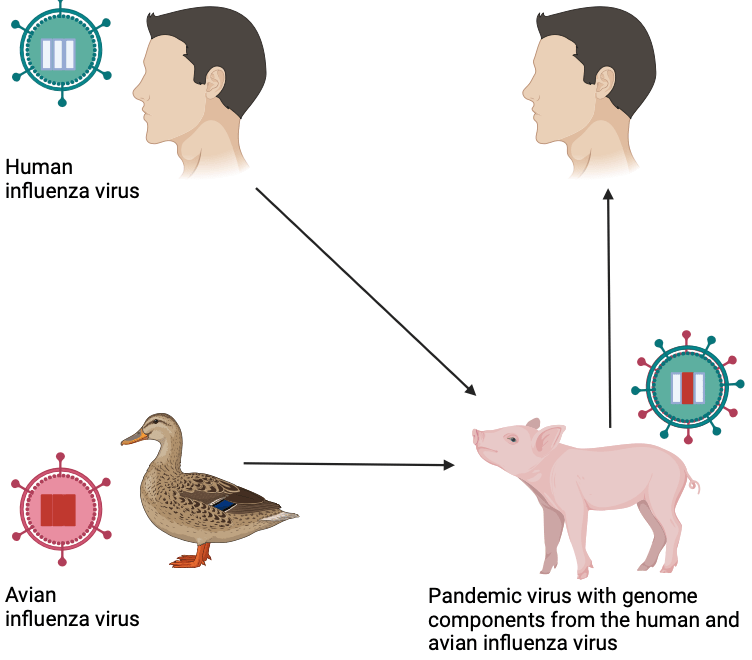

Pandemics occur when an avian influenza virus and a human influenza virus infect pigs causing the virus genome to be re-assorted giving rise to new variants. These new variants have different proteins on the virus surface that are not recognised by the human immune system and are adapted well to infect humans.

By pushing species into densely packed areas viruses are more likely to make the jump from animals to humans as well as from humans to animals increasing new and possibly catastrophic diseases to animals and humans alike (17). This has concerning implications for both animal conservation and human health (18). Climate change is likely to become the greatest risk factor for pandemics, greater than wildlife trade and poor agricultural practices (18). The scary thing is that Carlson and colleagues found that keeping the temperature rise under 2 degrees Celsius will not reduce the likelihood of this happening (17).

What can you do?

This blog has been quite scary, but I’ll end it on a more positive note. There are tonnes of things you can do at home to help mediate the impacts of climate change. These include large-scale projects like installing solar panels, planting trees, and investing in an electric car to small-scale shifts in your way of living through buying second-hand, using public transport, eating less meat and keeping informed (11). No matter how small or big an action you may do, it all adds up to lowering our carbon footprint and brings us closer to net zero.

By Francesca Giannachi-Kaye

Reference List:

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-58874518

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/greenhouse-effect-our-planet/

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/11/net-zero-emissions-cop26-climate-change/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/mar/18/carbon-capture-storage-technologies

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-58874518

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/58160547

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/58160547

- https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/net-zero-target-set

- https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/net-zero-targets

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/greenhouse-effect-our-planet/

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zq2m2v4#z3727yc

- https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo692

- https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ecs2.4420

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7187803/

- https://www.who.int/news/item/30-11-2023-who-s-annual-malaria-report-spotlights-the-growing-threat-of-climate-change

- https://www.sciencealert.com/malaria-carrying-mosquitos-are-expanding-their-territory-almost-3-miles-a-year

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04788-w

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/04/220428085820.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4012789/#:~:text=Although%20apparently%20not%20pathogenic%20in,and%20Nipah%20and%20Hendra%20viruses.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7187803/

- https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/distribution.html#:~:text=The%20highest%20transmission%20is%20found,tolerant%20of%20lower%20ambient%20temperatures.